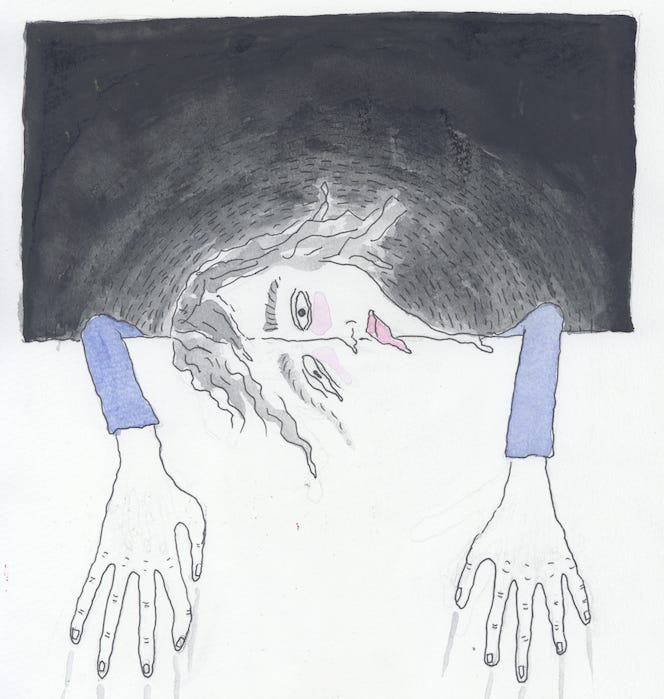

These days, time feels viscous and slow. I move through the hours half-reading, half-scrolling, not quite landing anywhere. I’m drifting. After the end of an 18 year relationship, everything feels suspended. I’m wading through something (grief, loneliness, the ambient ache of loneliness). The dizziness of freedom, as Kierkegaard put it: the terror of too many paths and no clear direction.

There’s a particular kind of heat in July that makes the world feel hazy and out of focus. Everything is shimmering, reluctant to cohere. The fan lazily turns. The glass sweats. I forget what day it is. There is no schedule, no shared Google Calendar, no partner returning at seven. The domestic gravity of my old life has fallen away, and I am untethered. It’s supposed to feel liberating. Sometimes it does. But mostly it feels like when you realize you’ve floated too far from your towel on the beach. Not panicked, just disoriented. Lost.

It’s hard to read, or rather, I read the same paragraph four times and give up. My mind, once sharp and hungry, now hovers somewhere between distraction and apathy. I used to think with more clarity. Everything I reach for slips through my fingers (books, plans, reasons not to buy a Dyson Airwrap). The only things I seem capable of doing are scrolling TikTok for skincare routines I’ll never follow and researching overpriced hair tools as if they might give me a self to step into. I don’t buy them. I just linger in the fantasy of becoming someone with smooth, controlled edges.

Kierkegaard says anxiety, that dizziness of freedom, is caused by the sheer volume of possibilities coupled with the unbearable fact that we must choose. We start catastrophizing, fearing we made the wrong choices, worrying about future outcomes we have no control over. And once we choose, we’re responsible for the choice. So we spiral. What if I pick wrong? What if I already did?

I’m in that limbo of decision-making: What job will I get? What health insurance? How? Who else might I love? KG calls the associated emotional state despair. He argues that most people spend their lives trying to flee despair, to distract themselves from the frightening fact of their own freedom. We long to forget that we are free. As Stephen West puts it, despair is “herpes of the spirit.” It’s a latent, symptomless disease that’s always inside you, dormant, waiting to sprout a hideous cold sore the night before your first date with Time’s Bachelor of the Year.

One of the most common symptoms of despair is mistaking our worth for something external: I’ll be okay if I get that job. If I remarry. If my kid does well in school. But the bar always moves. The thing arrives, and the emptiness returns. We despair.

And the medicine, apparently, is to stay with the emptiness. To feel the anxiety and recognize it not as failure, but as evidence of freedom. It means you’re alive. I hate this answer. It makes me want to add the hair dryer to my cart.

Loneliness in summer is a strange thing. It doesn’t feel gothic or tragic; it feels bright and expansive, like a blank page I don’t have the energy to fill. Grief isn’t always cinematic. Sometimes it’s just a long afternoon with nowhere to go. Sometimes it’s making a super sad (Carb Smart Tortilla-based) dinner for one and realizing you haven’t spoken out loud all day to anyone other than cats. There’s a quality of invisibility to it. I am still here, but thinner. Translucent. As if the world is looking past me, waiting for me to solidify.

And yet: I am not unhappy. Or not only unhappy. There’s a kind of quiet, though merciless, beauty in this drift. I notice the clouds through the balcony window. I feel the ache without rushing to soothe it. Maybe this is what it means to grieve: not to fix, or plan, or transform, but to float in the in-between until something new begins to take shape.

So I make a little food. I take a walk. I reread a poem I used to love. I don’t buy the hair dryer (I might still buy the hair dryer). I don’t decide anything. I drift.